The strike was a disaster, and in the end the Journeymen lost. They returned to work at the old wage, and the New York City Journeyman Plumbers Society was badly damaged by the strike. The general public was extremely upset and blamed both sides for the inconveniences the residents of the city had suffered during the strike.

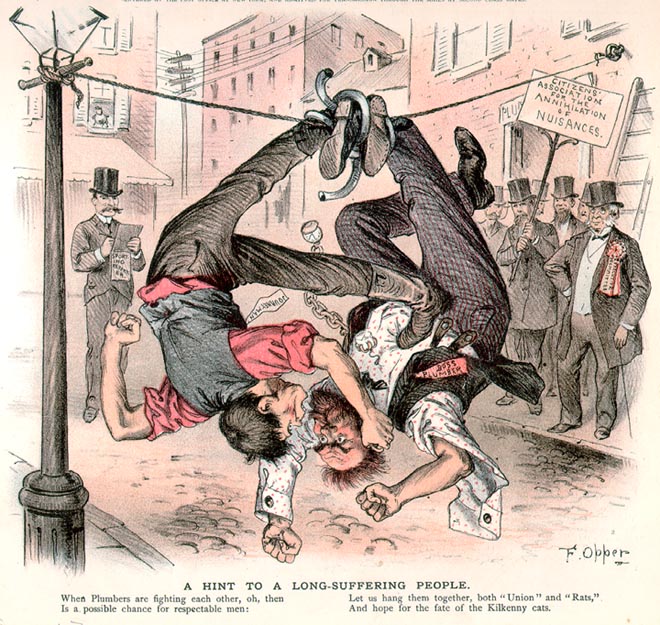

During the 1882 New York City plumbers strike,

the news magazine PUCK published this political cartoon capturing the

feelings of the day (Note the red dots on the shirt of the Boss Plumber

indicating that he is only slightly advanced from the Journeyman in a red work

shirt, their legs tied together by lead pipe).

Following the unsuccessful

strike of 1882, the New York City Journeymen Plumbers Protective Society

decided to join up with the Knights of Labor. The Knights were a secret society

which had its roots in the labor movement of Philadelphia. They had formed initially

as a single craft union (garment cutters), but had adopted a philosophy of

uniting all labor in a broad union. By accepting members from other trades,

known as “sojourners”, they began to expand. By 1882 they were becoming a

rapidly growing national movement. Secrecy was initially a big part of their

rituals, and they were arranged in groups called “Assemblies”. The New York

City Journeymen Plumbers Society became Local Assembly 1992 of the Knights of

Labor. Affiliation with the Knights contributed greatly to the recovery of the

local, and a pay raise was negotiated without another strike. The grouping of

so many trades under one umbrella made business owners and some public

officials nervous, and encouraged negotiation rather than allowing a strike to

start. The Gas-Fitting trade was booming in these years, and while in New York

City the trades operated separate plumbers and gas-fitters local organizations,

in Brooklyn they had long been combined. The Brooklyn Plumbers and Gas-Fitters

Association subsequently joined the Knights with the assistance of the New York

Local Assembly 1992 plumbers.

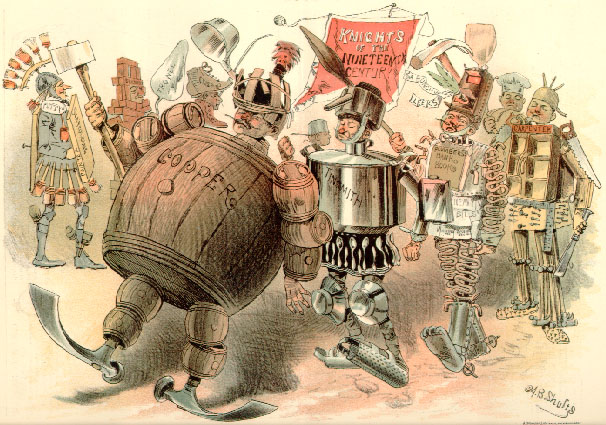

A political cartoon of the time ridiculed the

Knights.

(Marcher #3 is the Plumber)

The 1880’s became a

period of great prosperity in the building trades, and by 1884 there

were in the New York City area five local assemblies of the Knights composed

solely of pipe trades craftsmen. The Steamfitters in New York City organized

themselves as the “Enterprise Association” in that same year of 1884 and shortly

joined the Knights as Local Assembly 3189.

Under the Knights, the

journeymen plumbers and gas-fitters in New York City and Brooklyn originally

flourished, adding new members and enjoying the prestige of being part of a

large national movement, but within a few years there was trouble. The plumbers

Local Assemblies were under the authority of District Assembly 49 which

comprised many crafts and mixed assemblies of Knights locals in New York City.

The plumbers felt that District Assembly 49 was not operating in the best

interests of the pipe trades. Under the Knights constitution it was possible to

organize district assemblies or even “national trade assemblies” of one

particular craft. The formation of a pipe trades craft assembly in New York

would save the local unions of plumbers, gas fitters, and steamfitters

considerable amounts of money which, instead of being sent to District Assembly

49, could be used for the furthering of interests of journeymen in the pipe

trades. Perhaps more importantly, it would also free the pipe trades locals

from the interference of the leaders of District Assembly 49.

They organized a

conference. The result was the formation of the “National Association of

Plumbers, Steamfitters, and Gasfitters” led by Patrick Coyle, a prominent

member of the New York City plumbers union. This was originally intended to be

a national organization within the Knights of Labor, perhaps to be recognized

as its own national trade assembly, but it was never sanctioned as its own

national trade assembly by the Knights. “The National” continued to operate

unofficially, organizing locals in several cities. By 1885 there was

confusion among the New York City plumbers.

Many had joined the

National Association, but still held membership under the Knights. The

situation came to a head when the leaders of the Knights, perhaps fearful of

losing the pipe trades altogether, granted an earlier request of the New York City

plumbers and Brooklyn plumbers & gas-fitters local assemblies to start

their own District Assembly. The new District Assembly 85 was a Knights of

Labor body composed of several unions of plumbers, gas-fitters, and

steamfitters which would no longer have to answer to District Assembly 49.

When the National

Association of Plumbers, Steamfitters, and Gasfitters held its annual

convention later in 1885, they concluded that the formation of District

Assembly 85 in New York proved that the Knights were never going to recognize a

larger national trade assembly of pipe trades, and voted to break with the

Knights, establishing an independent national trade union. With the inclusion

of some Canadian locals, they also changed their name to “International

Association of Journeyman Plumbers, Steamfitters, and Gas-fitters”.

A breakdown of unity

resulted, particularly in New York City. The I.A.J.P.S.G. grew in strength,

adding seventeen locals around the country throughout 1885 and 1886, but the

New York City and Brooklyn locals formally withdrew from the I.A.J.P.S.G. in

1886. The reason for this was that the membership of the New York City and

Brooklyn assemblies, all of them in District Assembly 85, refused to be

affiliated with an organization outside the Knights of Labor. They also had

been favorably discussing with the leader of the Knights, Grand Master Workman

Terrance Powderly, the upgrading of District Assembly 85 to a national trade assembly

within the Knights.

In June 1886 New York

City and Brooklyn received a charter from the Knights to set up a national

trade assembly. A preliminary convention was held in Brooklyn, and the new

organization was formally named the “United Progressive Plumbers, Steam and Gas-Fitters,

National Trade Assembly No. 85” of the Knights of Labor. Now there were two

national unions in the pipe trades.

1886 was turning out to

be the most critical year in the history of the plumbers union in New York. New

York City local assembly 1992 of the Knights of Labor called another strike.

This was an unusual strike because it did not center on wages or hours. The

only issue was apprenticeship rules; there was no disagreement on other

matters. The employers wanted complete control over apprenticeship. The union

demanded a ratio be established at one apprentice to four journeymen; on union

voice in acceptance of individual apprentices; and on union examinations for

apprentices to advance to journeymen. The 1886 strike dragged on for several

months and ended in complete union defeat. Local assembly 1992, which was the

core local of National Trade Assembly No. 85, was almost entirely destroyed. In

order to procure work, many members defected and organized a new local under

the I.A.J.P.S.G. This led to an all-out labor war, as former brother journeyman

plumbers, now in different locals under different national organizations,

battled for the same jobs in New York.

National Trade Assembly

No. 85 struggled on with the remnants of the New York plumbers local, the

Brooklyn plumbers & gas-fitters local, and the Enterprise Association

steamfitters in Local Assembly 3189 hanging together through 1887.

In 1888 the New York City steamfitters decided to quit National Trade

Assembly No. 85. They left to help found the “National Association of Steam and

Hot Water Fitters”. This additional blow to the Knights organization of pipe

trades in New York was severe.

The Brooklyn plumbers

& gas-fitters local was sticking together at home, but both of the national

plumbers unions were falling apart. The I.A.J.P.S.G. had gotten into financial

trouble and was struggling. As for the Knights of Labor, the whole organization

was in disarray. This was in part because of Terrance Powderly’s refusal to

allow “Trade Unions” to form within the Knights, and also due to devastating

strikes by Knights in coal mining and railroads.

There were still

feelings that somehow a strong international union of pipe trades could be

formed. The leaders of National Trade Assembly No. 85 began to correspond on

the issue. They contacted locals of the now bankrupt I.A.J.P.S.G., as well as

bigger independent locals like the Boston plumbers. A positive correspondence

between National Trade Assembly No. 85 secretary-treasurer Richard A. O’Brien

of Washington D.C., and Boston independent plumbers’ leader

Patrick Quinlan, encouraged the Brooklyn based leadership

of National Trade Assembly No. 85 to call for a meeting.

The meeting was held in

Brooklyn, July 29 through 31, 1889, and delegates were invited from all the

locals of the I.A.J.P.S.G., National Trade Assembly No. 85, and all the

independent unions known to exist. The meeting was attended by about a hundred

delegates. The discussions were favorable to the formation of a new single

international union to represent the pipe trades. They elected an executive

committee of three representatives; one representative from National Trade

Assembly No. 85, one from the I.A.J.P.S.G., and one to represent the

independent locals. This group of three then scheduled the founding convention

of what would become the “United Association of Journeyman Plumbers, Gas Fitters,

Steam Fitters, and Steam Fitters’ Helpers of the United States and Canada” or

the “U.A.”.

They set the date of

that meeting for October 7 through October 11, 1889 in Washington D.C., and in

accordance with the instructions given during the Brooklyn meeting, each local

was entitled to send one delegate for one hundred members or less, and one

additional delegate for each majority fraction of one hundred members. In the

Brooklyn Daily Eagle of December 19, 1889 there is recorded the following:

At the 1889 “Founding

Convention” of the United Association, the Brooklyn delegates were very

influential, since most of the founding locals were members of the Knights of

Labor National Trade Assembly No. 85, which Brooklyn had been running since the

devastating New York City strike of 1886. Brooklyn also had more members, and

more delegates than any other local represented. The Brooklyn local became

Local No. 1, and New York City was designated as Local No. 2. The date now

recognized as the founding of the United Association was the final day of this

convention, Friday, October 11, 1889.

The delegates from the Brooklyn and New York

City plumbers’ locals at the 1889 “Founding Convention” of the United

Association were as follows:

D. Cassin – Brooklyn, James Rankin – New York, T. Kinsella – New York,

P.H. Gleeson – Brooklyn,

H. Fox – Brooklyn, D. Hodgens – Brooklyn,

M.J. Driscoll – Brooklyn,

M.F. Murray – New York (Gas Fitters),

John Todd – Brooklyn, M.F. Dolan – Brooklyn (Eastern District) - Williamsburg

For the most part, the

Steamfitters did not participate, because they were still trying to set up

their own national union known as the “International Association of Steam and

Hot Water Fitters” or the “I.A.”. Not one local made up solely of steamfitters

actually joined the United Association at the “Founding Convention” of 1889.

The United Association held its next convention in Pittsburgh in 1890.

The delegates from the New York plumbers’

locals at the 1890 “First Annual” United Association Convention were as

follows:

James J. Doody – LU1, Augustus Esser – LU1, John Hand – LU1,

Michael Driscoll – LU1, James F. Hickey – LU1, John J. O’Connell – LU1,

William J. Carey – LU2, Edward Farrell – LU2, William W. O’Keefe – LU2,

James Laverty – LU6, William Till – LU6, (Note: LU6 – Brooklyn East)